LAYERS OF TRAUMA DURING COMPLEX ABUSE

Most recipients of avoidant abuse can cycle repeatedly through the stages. Following a period of renewed distress the recipient may try another method to obtain relief. If a previous attempt - such as engaging with the avoider - did not bring positive results, they may try going to mutual parties for support. If that fails they can revert back to a renewed period of distress before trying another method to try and improve the situation.

Every time a new method is ineffective or

backfires, recipients typically experience another period of despair.

In

addition, some of the options at the third stage - such as re-engaging with the

avoider or seeking support from mutual parties - can lead to new 'rounds' of

abuse. For example, abusers may provoke the recipient by baiting them, employing

techniques of gaslighting, conducting smear campaigns or recruiting proxies to

attack the target on behalf of themselves. This can greatly increase the

complexity of the trauma experience for the recipient, as well as extend the

duration of time over which they are subjected to abuse.

Going

to external sources for help can also be unsatisfactory as a lack of awareness

- along with counterproductive 'advice' - can lead to doubt and confusion, which

in turn can lead to re-traumatisation and 'trigger' feelings of distress and

emotional upheaval. This can complicate and extend the process of resolution

even further.

This repetitive cycling through the stages - which is often experienced more than once - forms the classic 'back and forth' process many recipients of avoidant abuse experience. As the trauma repeats and gets longer drawn out, the abuse and its resultant effect increases in complexity and magnitude.

So how can the cycle be broken? Is 'no contact' the only way (or even a legitimate way) to respond?

Is there a better way to respond to avoidance, banishment and excommunication?

The answer is to look at the abuse trauma experience in a completely new and different way.

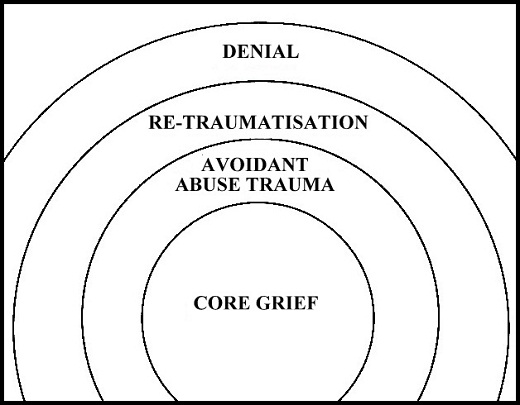

This means seeing the trauma as a layered phenomenon, rather than simply as a 'stage by stage' process.

'Layers' of Trauma

Experiencing avoidant abuse can be a complex and

continuous traumatic experience. Without disengagement, its effects can build

up over time - making it uniquely challenging to work through. Effective

support for recipients thus - rather

than focusing directly or solely on just one isolated event or one aspect of

the trauma - needs to include a more holistic approach which can address the

entirety of their traumatic experience.

Here, we take up a unique, ‘integrated’

approach which is particularly suited to the peculiar nature of avoidant abuse

trauma. By viewing the recipient’s experience as a 'layered' trauma, it becomes

possible to address and work through each

'layer' sequentially, as part of a holistic process to help recipients reach

resolution. As per this view, avoidant abuse trauma can be considered to

consist of the following main 'layers' :

Outer Layer : Denial

Secondary Layer : Re-traumatisation

Primary Layer : Abuse Trauma

The Nucleus : Core Grief

The Outer Layer : Denial

The first ‘layer’

that we come across lies at the outermost level, almost acting like a ‘façade’.

This layer is usually characterized by an attitude of ‘denial’ which can often

be expressed in the form of pretending not to care, acting at being 'over it' -

when the problem situation is not yet resolved, nor has true disengagement

occurred. This attitude can consist of a basic avoidance response to deal with

a complex trauma experience which can seem just too painful and confusing to

ever be truly 'healed'.

With

the abuse ‘covered up’ and denied, there can be considerable resistance to even

begin to 'open up' and address the trauma in its entirety. Breaking through

this barrier of resistance thus becomes a primary step for many recipients.

The Secondary Layer : Re-victimization

and Re-traumatisation

One level 'below'

the layer of 'denial', lies the layer of ‘re-traumatisation’. This can largely

be made up of ongoing experiences of invalidation of the recipient's trauma,

the non-recognition, denial and dismissal of the abuse (whether by the abuser,

or by others turned to for support and understanding), as well as due to doubtful

or false justifications which can excuse or legitimize the abuse behaviour. Vulnerable recipients often adopt questionable

and even harmful beliefs (and habits) as a result of unawareness and a

profusion of inappropriate 'advice'. This is the 'layer' in which 'triggers'

can be embedded.

In

addressing re-traumatisation, it becomes crucial to challenge and question many

prevalent ideas and beliefs relating to relationships, abuse, and relationship

dissolutions - which may be totally inappropriate in the context of avoidant

abuse.

The Primary Layer : Abuse Trauma

Abuse trauma is

the most complex 'layer', which can be challenging to work through as it can

consist of multiple trauma experiences which occur not only as a response to

abuse strategies which attack, but also those which re-attack the

target, making it a continuous trauma and not a once off experience. For

example, simple absence such as cutoff, ghosting or banishment can cause the

primary trauma. Strategies which follow as a result of baiting tactics - such

as social abuse campaigns and excommunication - can cause more complex trauma.

In addition, the effects of psychological manipulation can make the

comprehension of events even more obscure for the recipient, who may be falsely

accused, and yet unable to realise they were baited and provoked, or unable to

perceive the falseness of the allegations.

In

addition to the abuse strategies, the recipient may also need to deal with the

realisation and acceptance of the fact that a significant, loved and trusted

individual has chosen to enact the abuse - and this realisation can include

feelings of betrayal and disappointment. The views and opinions of the abusive

individual - which can often include unjustified hatred, evil intent, disvalue

and disrespect - can also be difficult to accept or even to comprehend.

The Nucleus : Core Grief At the heart of the 'layers' exists what can be

described as the 'core' grief. It can be the fundamental, ‘pure’ grief which is

not necessarily connected with the abuse. It could be related to the ending of

a significant relationship or of a phase of one's life, the loss of love or

happiness, the loss of a valued individual from one's life or of a possible

life or future that could have been.

Addressing the

'Layers'

It is not just

the complexity of avoidant abuse trauma which is underestimated - its very

nature can frequently be misunderstood. To understand the reason for this, we

need to revisit a crucial point that was mentioned earlier about the harmful

nature of avoidance - that is, that avoidant behaviour in itself is so

destructive in nature, that its practice almost always results in the disintegration of relationships. What this

means is that avoidant abuse is almost always experienced by recipients in

conjunction with relationship dissolution.

Avoidant

abuse is almost always experienced by recipients in conjunction with relationship dissolution

The fundamental

difference however, between a relationship separation marred by avoidant abuse,

and one which is not abusive (as well as different from bereavement), is that

abuse includes the conscious decision by the significant other, to

engage in behaviour which is intended to harm and cause suffering to the

recipient. It is this feature which results

in two simultaneous experiences - one, the 'core' grief - arising mainly as a

result of the relationship dissolution, and the other, the abuse trauma - which occurs as a result of the enactment of

behaviour intended to cause harm.

As

this distinction is often not recognised, a common mistake many make is

to automatically assume that the suffering of the recipient occurs only due

to the grief of the dissolution - or the 'core' grief - without realising that

it largely arises as a response to abuse.

Unawareness

regarding avoidant abuse can lead to recipients addressing (and being advised

on) only their grief response and not

the abuse trauma - when both actually occur in conjunction. As a result of this amalgamation, both the grief and the trauma can be perceived by recipients as one 'combined' experience. Often, recipients who feel as if they are unable to 'move on' can mistakenly interpret it as 'attachment' or 'heartbreak' grief or trauma over 'rejection' - without recognising that it may largely be occurring as a response to abuse.

On the flip side, many online amateur 'narcissistic abuse' forums see the trauma as arising ONLY from the abuse, and call it 'trauma bonding' due to intermittent reinforcement. While there is some truth to this, it is not the whole story. In terms of CBT based and family systems therapy, the cognitive dissonance can be seen to arise due to the inability to reconcile the two contrasting aspects of the abuser - the good 'lovable' aspect, and the 'cruel abusive' aspect. It is this inability which causes the cognitive dissonance, leading to 'emotional fusion' an unhealthy attachment) which is popularly referred to as 'trauma bonding'. This emotional fusion can be overcome by developing resilience. Further on we will see the specific ways in which emotional resilience is built so that emotional fusion (or trauma bonding) is weakened.

For many, what

can be most challenging upon recognising the abusive behaviour, is to then be

able to differentiate the abuse trauma from the 'core' grief. If these

two are not clearly distinguished, they can feel as one insurmountable

confusing heap of 'emotional baggage' which never fully seems to resolve. A

crucial step for avoidant abuse recipients is thus to be able to differentiate the

abuse trauma from the 'core' grief

"GOOD PAIN AND BAD PAIN"

A basic

difference between 'core' grief and abuse trauma can be seen to lie in their

fundamental nature. In simple terms, the former can be identified as a 'good'

pain, while abuse trauma can be considered to be a 'bad' pain. 'Core' grief is

largely a 'blameless' grief - it is a grief that is no one's 'fault', which

would have existed upon the dissolution of the relationship even if the abuse

had not taken place. It is very different from the trauma arising from abuse

which is generally deliberate and pre-planned in nature.

'Core'

grief can largely be related to the 'losses' of the 'good' things - and in this

sense it can be seen as an experience which - while painful - can still be

considered 'benign' in nature - one which consists of realisations that need to

be acknowledged authentically and not resisted. Abuse trauma on the other hand,

is a largely an unnecessary pain. It

can be considered a 'bad' pain which does not 'help', but which can hinder

disengagement and extend the grief processing. The 'core' grief can - if dealt

with directly - offer closure naturally - akin to the idea that ‘the only

way through grief is through it’. But abuse trauma can 'block' this process

and prevent disengagement and resolution.

When

a relationship dissolution is accompanied with abuse, what recipients can be

most distressed by, are not the

'losses' (of the person or relationship) of the 'core' grief - but rather the manner

in which things were conducted. No matter how much an individual

or previous relationship is desired or missed, respectful and compassionate

conduct during separation can enable one to bear the pain of loss. Secrecy, deceit and abuse on the other hand, can diminish one's innate resilience

which can make the experience of separation far more traumatic and painful than

it needs to be, because the psychological mechanisms which can help to bear the transition, can be 'wounded'.

This difference

between 'good pain' and 'bad pain' is also reflected in the difference between

the pain of knowing versus the pain of not knowing. The pain of

knowing truths - even difficult truths - is usually a 'good' pain which can

lead to clarity, resolution and even evolution. The pain of 'not knowing'

however, can act as a terrible wound which can fester for years without

respite.

A core weakness of habitual 'avoiders'

is their refusal or inability to distinguish between 'good' pain and 'bad' pain

There is thus a fundamental difference between the

kind of pain which while being bitter, can be 'medicinal' and heal, and that

which can be toxic and 'eat away' at a 'wound'. The pain of ‘not knowing’ is

almost always a worse pain than the pain of ‘knowing’ - which while unpleasant

initially can ultimately lead to improving the situation. A core weakness of

many who habitually employ avoidant tactics40 and keep secrets to

avoid the 'discomfort' of authenticity and transparency, is the refusal or

inability to distinguish between 'good' pain and 'bad' pain. When the unnecessary

and toxic pain of secrets, lies, denial and silence become a habit, growth and

evolution - whether in a relationship context or as an individual - remains

stagnant.

It is not just

the combination of core grief and abuse trauma which makes avoidant abuse

trauma particularly complex. In addition to these two, re-traumatisation too,

can be combined with abuse trauma in the perception of the recipient. As we

know, re-traumatisation can occur as a result of being subjected to

inappropriate or unsuitable 'advice', or being the subject of mistaken

assumptions which can occur during efforts made by the recipient to improve

their situation following the abuse. As a result, experiences of

re-traumatisation are generally encountered prior to (or in place of)

finding suitable and effective support. This 'layer' hence ends up adding to

the complexity of the entire trauma experience, and can result in a longer and

more complicated recovery process. It thus needs to be recognised, addressed and

worked on before moving on to the

primary or 'core' grief or even the abuse trauma.

On

top of all these, there can exist the most superficial 'layer' of denial which

can arise as a result of avoidance coping. This is often exacerbated by methods applied wrongly such as going 'no contact' in response to the abuser. The result? ongoing trauma damage, poorer functioning in subsequent relationships, repeated patterns of attracting abusive partners, and more.

Breaking through this 'barrier' can

be the initial challenge - especially when recipients are not yet ready to

acknowledge or address their trauma and grief. In some cases, when years have

gone by since the start of the abuse, substantial work may need to be done in

order to re-frame thinking and processing patterns before one can even start to

move on to the re-traumatisation, abuse trauma and 'core' grief.

Further ahead we

will look at the process of working through these 'layers' of trauma with

better, more effective approaches, which can include 'exposure',

'accountability' and acknowledgement of the ‘truth’, while focusing on

formulating a response to the abuse in a way which honours oneself and one's

own experience. We will look at different ways in which recipients can learn to

respond more effectively to avoidant abuse strategies, as well as learn to

function more optimally after experiencing abuse trauma. We will see how the taking

up of various steps can contribute towards true healing and enable recipients

to move forward more enriched and empowered than before.

(book excerpt)

© 2015 Avoidant Abuse - The Abuse Technique of the New Age

ISBN 978-0-9942430-4-1

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511-524.

Heavey, C. L., Christensen, A., & Malamuth, N. M. (1995). The longitudinal impact of demand and withdrawal during marital conflict. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 797–801.

Hubble, M. A., Duncan, B. L. & Miller, S. D. (1999). The Heart & Soul of Change: What Works in Therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Mayer, B. S. (2015). The Conflict Paradox: Seven Dilemmas at the Core of Disputes. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley &Sons.

McCraken, J. (2005). Falsely, Sanely, Shallowly: Reflections on the Special Character of grief, International Journal of Applied Philosphy 19(1), 139-156.

Rosenberg, R. (2013). The Human Magnet Syndrome: Why We Love People Who Hurt Us. Eau claire, WI: PESI Pub. & Media.

Sanderson, C. (2008). Counselling Survivors of Domestic Abuse. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Stroebe, M. S., Hansson, R. O., Schut, H. E., Stroebe, W. E., & Van den Blink, E. I. (2008). Handbook of bereavement research and practice: Advances in theory and intervention. American Psychological Association.

Titelman, P. (2003). Emotional Cutoff: Bowen Family Systems Theory Perspectives. New York: Haworth Clinical Practice.

Vaughan, D. (1986). Uncoupling: Turning Points in Intimate Relationships. New York: Oxford University Press.

Visser, F. (2003). Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion. Albany, NY: State U of New York.